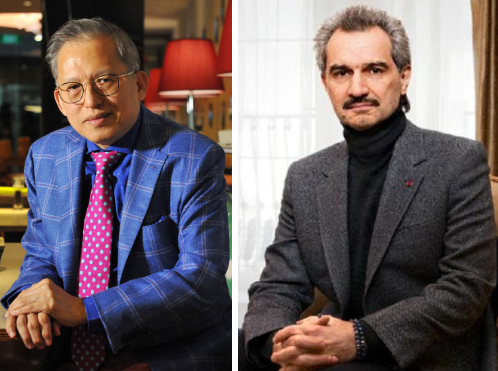

The Plaza Hotel was opened in 1907 and has become a New York icon. The hotel has changed hands several times since its establishment, one of whom was Hong Leong Group Executive Chairman Kwek Leng Beng, who purchased the hotel in 1995 with Prince Alwaleed bin Talal of Saudi Arabia. (Photo credit: Shutterstock)

The Plaza Hotel was opened in 1907 and has become a New York icon. The hotel has changed hands several times since its establishment, one of whom was Hong Leong Group Executive Chairman Kwek Leng Beng, who purchased the hotel in 1995 with Prince Alwaleed bin Talal of Saudi Arabia. (Photo credit: Shutterstock)

The Plaza

Hotel:

The Legend

Behind

New York’s

Most Iconic

Hotel

The Plaza Hotel is undoubtedly a New York icon. Opened in 1907, the Midtown Manhattan hotel plays host to New York’s ultra-wealthy, US and foreign dignitaries, and internationally-known celebrities on the regular.

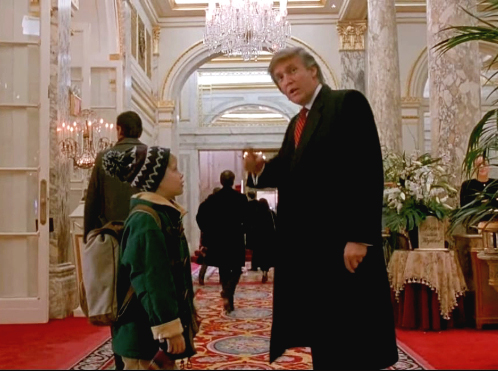

Accorded landmark status in 1969, the hotel has also held starring roles in a number of Hollywood films, including Home Alone 2: Lost in New York and The Great Gatsby (both the 1974 and 2013). It also appeared on the political stage, as the Plaza Accord, a joint-agreement between France, West Germany, Japan, US and the UK signed in 1985, was named after the hotel where the meeting took place.

Since its opening, the hotel has seen many owners come and go, including Hong Leong Group Executive Chairman Kwek Leng Beng who purchased the hotel with joint venture partner Prince Alwaleed bin Talal of Saudi Arabia in 1995 for US$325 million from Donald Trump. Mr Trump bought the hotel seven years earlier for US$408 million. Read more about this interesting chapter in the hotel’s history, adapted from The Plaza: The Secret Life of America’s Most Famous Hotel by Julie Satow.

In 1992, then-owner Donald Trump (who purchased the hotel in 1988) lost the hotel to his bankers. In a bankruptcy filing that ran almost 1,500 pages, reams of unpaid creditors were listed, including the New York State, Manhattan Limousine, and Atlas Floral Decorators. In total, the Plaza’s assets were listed as $375 million, but its liabilities ran to nearly $480 million.

The Chapter 11 filing was what is known as a prepackaged bankruptcy. By the time they filed, Trump and his lenders had already hammered out a deal, with Trump agreeing to hand over 49% of the Plaza to Citibank and a consortium of other lenders in exchange for easing the terms on his debt. While Trump nominally retained 51% of the hotel, it was only on paper, since he had no equity in the deal.

For the Plaza, it was the first time the hotel was bankrupt since its opening, and it was a demoralising blow.

Now bankrupt, the hotel’s creditors were anxious to sell the hotel to recoup at least some of their original investment. It was a race to the finish line between Trump and Citibank. If Citibank and the other lenders found a buyer for the Plaza, Trump would lose the property. But if Trump could identify a buyer first, he might convince that person to let him continue managing the hotel, or, perhaps, give him the go-ahead to complete his Plaza penthouses.

The Trump camp’s most promising lead was Sun Hung Kai & Co., one of China’s largest property companies. It was run by the three Kwok brothers, who were among the richest families in all of Asia. Walter Kwok, the eldest brother, was sufficiently intrigued at the prospect of purchasing the Plaza to come for a visit. With his wife, Wendy, and their children in tow, the family was put up in the lavish Presidential Suite.

However, an incident with a jammed door at the suite ruined the chances of selling the property to the Kwoks. Walter Kwok said that “the Plaza was too old, and it would cost too much to renovate. There was simply no way to justify buying the hotel under these circumstances.”

However, before Trump’s team could line up a new Plaza buyer, Citibank beat them to the finish line. The bank found not just one credible candidate with deep pockets, but two.

Left photo: In 1995, Hong Leong Group Executive Chairman Kwek Leng Beng and Prince Alwaleed bin Talal of Saudi Arabia purchased the trophy Plaza Hotel from Donald Trump at US$325 million. It was a steal of a deal considering that Trump had paid US$408 million when he first bought the property in 1988 and eventually led to its bankruptcy for the first time since its opening in 1907. Right photo: Trump had a cameo appearance alongside actor Macaulay Culkin in the 1992 blockbuster film “Home Alone 2”, which was filmed at the hotel. (credit: eTurboNews)

In 1994, two years into the Plaza’s bankruptcy, Citibank began discussions with Kwek Leng Beng, a billionaire property developer from Singapore. Kwek had recently bought two hotels in Manhattan, the Millennium Hotel located downtown, and the Hotel Macklowe, in Midtown. “One of my principal bankers at Citibank approached me and asked me to look at the Plaza,” Kwek told me. The hotel was well-located and historic, and “had the potential of generating large profits.”

As Kwek was conducting due diligence on the Plaza, Citibank called him again. This time, it was to tell him that Prince Alwaleed bin Talal of Saudi Arabia, a fellow billionaire who also happened to the bank’s largest private shareholder, was also interested in purchasing the property. “I [got] a call to say that Prince Alwaleed would like to form a joint venture with me on the Plaza,” said Kwek. Soon, the two billionaires were partnered.

Before the deal went through Trump met with Kwek in London, where the Singaporean’s hotel chain was based. He proposed that Mr Kwek take him as a partner, rather than the prince.” Kwek declined the offer, possibly because Trump’s empire was in tatters and he had already bankrupted the Plaza. Trump, undeterred, then asked whether Kwek would allow him to continue managing the hotel. “Sorry, Mr Kwek responded: that job was going to the prince’s hotel company.”

Abraham Wallach, a Trump executive and faithful foot soldier then made himself a nuisance, trying to scuttle the deal. This included concealing himself in a secret room of the Plaza’s Vanderbilt Suite where the talks were taking place to eavesdrop and cause mischief. In another instance, which Wallach claims was Trump’s brainchild, the fire department was called, forcing everybody to vacate the building because it was deemed structurally unstable.

Eventually, Citibank and the other creditors apparently caught wind of the chicanery. The bank threatened to hold Trump’s other deals hostage unless Wallach halted his antics and allowed the sale to move forward. So in the end, Trump was forced to call Wallach off.

The current foyer of the two-room Vanderbilt Suite. It was where executives from Kwek Leng Beng and Alwaleed’s companies met to discuss the proposal in 1994 and 1995, and where Trump foot soldier Abraham Wallach hid himself in a secret room to eavesdrop. (Photo credit: The Plaza Hotel)

The current foyer of the two-room Vanderbilt Suite. It was where executives from Kwek Leng Beng and Alwaleed’s companies met to discuss the proposal in 1994 and 1995, and where Trump foot soldier Abraham Wallach hid himself in a secret room to eavesdrop. (Photo credit: The Plaza Hotel)

The current Palm Court which has been an iconic locale for afternoon tea since the hotel’s opening. It was renovated in 2013, and its signature feature, a soaring stained-glass dome, is modelled after the original built in 1907. (Photo credit: The Plaza Hotel)

The current Palm Court which has been an iconic locale for afternoon tea since the hotel’s opening. It was renovated in 2013, and its signature feature, a soaring stained-glass dome, is modelled after the original built in 1907. (Photo credit: The Plaza Hotel)

Trump had no choice but to give up the Plaza. He was in the midst of negotiating with Citibank and his other creditors to save what he could of his empire and he couldn’t risk it all falling apart on the basis of one hotel. So in April 1995, the deal with Kwek and Alwaleed finally closed. It valued the hotel at $325 million, or $83 million less than what Trump had paid seven years earlier. The transaction was complex, with Kwek and Alwaleed agreeing to reduce the outstanding debt on the hotel to about $25 million from more than $300 million, in exchange for each receiving a stake in the hotel of just under 42 percent. Citibank was also to stay in the deal, with a 16 percent equity stake.

Kwek told the Wall Street Journal that he wanted Citibank to remain an equity partner in the deal to ensure that Trump wouldn’t cause him any further trouble. Trump had a so-called right of first refusal, which allowed him to match any offer for the Plaza – an improbable scenario considering the state of his finances. While Trump was unlikely to execute that right, Citibank, as Trump’s lead lender, had leverage over him. By keeping Citibank in the deal, it provided additional insurance that Trump wouldn’t try to interrupt the sale. Several years later, Kwek and Alwaleed would purchase the remainder of the equity from Citibank to become fifty-fifty owners.

Kwek and Alwaleed also agreed to throw Trump a few scraps: If, under their ownership, the top floors of the Plaza were ever converted into penthouses, Trump would get a cut of the profits. He would also get a small fee if the hotel was sold within seven years. “I was a good listener when negotiating with Trump,” Kwek told me. “He wanted to continue managing the hotel and be part of the venture. We eventually narrowed down his role.”

Trump’s penthouses wouldn’t be built during Kwek and Alwaleed’s tenure as Plaza owners, and the hotel didn’t sell within the allotted time frame, so Trump never saw any profit from the deal. Despite coming out a loser, Trump insisted that he was a part of the new ownership. “We’ll be running the hotel. This is a joint venture. As a joint venture, everybody has input,” Trump told the New York Times. “There will be four partners in the deal,” insisted Wallach, naming Kwek, Alwaleed, Citibank, and “Mr Trump.”

With Kwek and Alwaleed at the helm, the hotel was under foreign ownership for the first time. Of course, the Plaza had long welcomed foreign guests and was a favourite of visiting dignitaries. But the acquisition of the hotel by the Singaporean billionaire and the Saudi prince (full name Prince Alwaleed bin Talal bin Abdulaziz Al Saud) indicated an increasing globalization of the real estate market. It was a trend that would only accelerate in future years. “The complexity of the sale announced yesterday and the international scope of the transaction, illustrated how the arenas of real estate and finance have grown beyond national boundaries, and how the business world has shrunk, in ways even the most visionary people could have hardly imagined when the Plaza opened in 1907,” wrote the New York Times about the deal back in 1995.

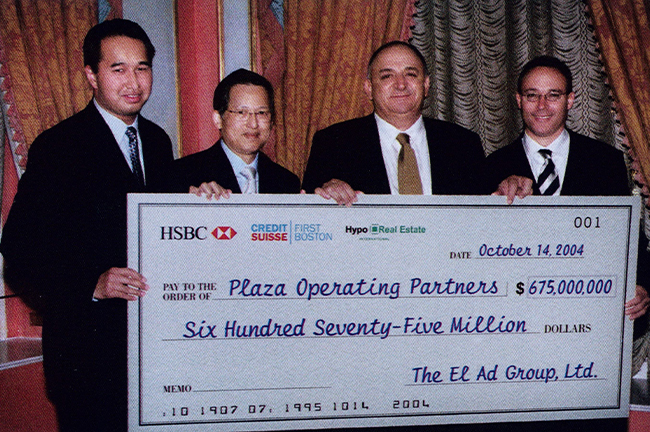

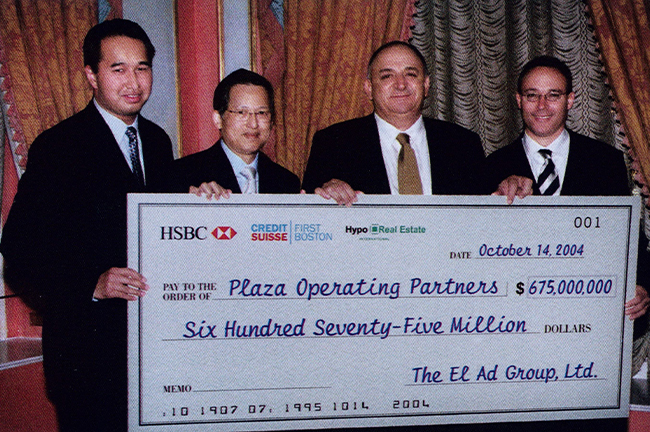

By 2004, the two owners were ready to offload the hotel. An ambitious Israeli-born condominium developer, Miki Naftali (far right), flew to Singapore and convinced Kwek Leng Beng to sell him the historic property. He is pictured here at the closing ceremony of the sale with his boss Isaac Tshuva (standing next to him), as well as Kwek and his son Sherman. The men hold a check representing the Plaza’s price tag, more than double the price Kwek and Alwaleed had paid when they acquired the property from Trump. (Photo credit: Steve Friedman, The Plaza: The Secret Life of America’s Most Famous Hotel/Julie Satow)

By 2004, the two owners were ready to offload the hotel. An ambitious Israeli-born condominium developer, Miki Naftali (far right), flew to Singapore and convinced Kwek Leng Beng to sell him the historic property. He is pictured here at the closing ceremony of the sale with his boss Isaac Tshuva (standing next to him), as well as Kwek and his son Sherman. The men hold a check representing the Plaza’s price tag, more than double the price Kwek and Alwaleed had paid when they acquired the property from Trump. (Photo credit: Steve Friedman, The Plaza: The Secret Life of America’s Most Famous Hotel/Julie Satow)

In 2004, the hotel was sold to El Ad, an Israeli condominium developer who carved much of the building into apartments. The remaining boutique hotel was then sold to an Indian tycoon. In October last year, the hotel changed hands once more when Qatar's Katara Hospitality's chairman Sheikh Nawaf Al-Thani acquired the Plaza.