(Left) A portrait of Mrs Caroline Astor by French painter Carolus-Duran which used to hang in the house. (Photo credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art) (Right) A photograph of Mrs Astor’s home along Fifth Avenue. (Photo credit: Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University)

(Left) A portrait of Mrs Caroline Astor by French painter Carolus-Duran which used to hang in the house. (Photo credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art) (Right) A photograph of Mrs Astor’s home along Fifth Avenue. (Photo credit: Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University)

Caroline Astor:

A Legacy

In Time

A look at the life of the doyenne of 19th century American high society, the inspiration behind Caroline's Mansion.

Converted from indoor tennis courts, Caroline’s Mansion is The St. Regis Singapore’s newest event space. It is a homage to the residential elements of Caroline Astor’s original home in New York. Aptly named “The Astor Double Mansion”, it was an early 16th century French Renaissance style large double house on the corner of 65th Street on Fifth Avenue. It was once the popular host venue for lavish events and the definitive place to see and be seen.

But who was she? Mrs Astor (September 21, 1830 – October 30, 1908) was the matriarch of St. Regis founder John Jacob Astor IV, who died in the 1912 sinking of the RMS Titanic. She was the New York socialite who ruled the city scene in the Gilded Age, an era defined by rapid economic growth and industrialisation in the United States during the 1870s to 1900. Known for her lavish balls and stringent adherence to social manners, Mrs. Astor established the family name as one that befits American wealth and privilege of the utmost degree.

Read more about this American ‘queen’ who dominated America’s high society of wealth and power, old money and tradition. This story is adapted from The Husband Hunters: Social Climbing in London and New York.

Born Caroline Webster Schermerhorn, Caroline was a prominent American socialite, whose family was a part of New York City’s Dutch aristocracy and had made its riches through shipping. In 1853, she married William Backhouse Astor Jr, whose family had made their fortune through fur trade and in real estate.

As huge fortunes were made in the aftermath of the Civil War which ended in 1865, many well-heeled immigrants and the nouveau riche came to New York City and wanted to display their new wealth in the most prestigious place of all – Caroline Astor’s social circle. Mrs Astor sought to codify behaviour and etiquette, and became the foremost authority on New York “Aristocracy”. Her prestige was such that to be invited to Mrs Astor’s annual ball was to be “in” society.

The signature Astor family portrait in the drawing room, which was decorated in the then-fashionable Rococo style. Caroline Astor married her husband William Backhouse Astor Jr (2nd from left) in 1853, and had five children, including St. Regis founder John Jacob Astor IV.

The signature Astor family portrait in the drawing room, which was decorated in the then-fashionable Rococo style. Caroline Astor married her husband William Backhouse Astor Jr (2nd from left) in 1853, and had five children, including St. Regis founder John Jacob Astor IV.  A portrait of Caroline Schermerhorn Astor in 1860.

A portrait of Caroline Schermerhorn Astor in 1860.

She had achieved this unchallenged position partly through her own personality and ambition, and partly with the assistance of social arbiter Ward McAllister. He was a socially ambitious man who realised that unless steps were taken to mold society into an acceptable model, it would be overwhelmed by the flood of new money pouring into New York. He managed to blend both old and new money by sifting through and picking the most socially desirable individuals from both groups, and saw Caroline Astor as the only person fit to rule this new elite.

She led The Four Hundred, a list of New York’s crème de la crème, for four decades. Ward McAllister reportedly coined the phrase “The Four Hundred”, and the number has also been popularly linked to the capacity of Mrs Astor’s ballroom at her home on Fifth Avenue.

Her greatest asset was her dignity, closely followed by her discretion – she is never known to have made a controversial remark. She could be friendly, but never intimate, and she never confided.

It might be hard for another woman to live down the behaviour of a husband such as Caroline’s, for William was known to be a heavy drinker and an even more voracious womanizer. Fortunately, both of these pursuits took place largely at sea aboard his yacht. As rumours of boatloads of chorus girls and a hold full of whiskey swirled around the New York social scene, Mrs Astor would smile serenely and remark – if anyone dared ask about him – that the sea air was good for dear William, while regretting that she could not accompany him as she was a poor sailor herself. For what Mrs Astor did not want to see, she did not see.

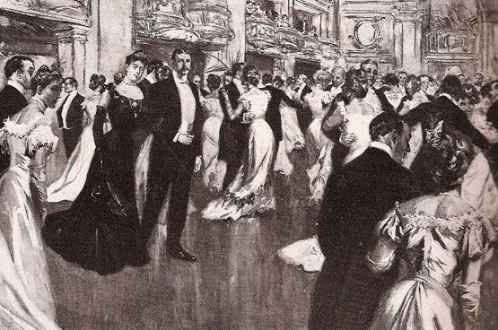

A portrait of Mrs Caroline Astor with Mr Elisha Dyer, former Republican governor of Rhode Island, at the Assembly Ball in New York in 1902.

A portrait of Mrs Caroline Astor with Mr Elisha Dyer, former Republican governor of Rhode Island, at the Assembly Ball in New York in 1902. Mrs Astor's drawing room where she entertained guests. It was one of the largest entertaining rooms (not including the ballroom), and complete with a resplendent gold ceiling, gold-framed mirrors and floors covered with oriental rugs, tiger rugs and leopard rugs. (Photo credit: Cesar Romero Robles/Flickr)

Mrs Astor's drawing room where she entertained guests. It was one of the largest entertaining rooms (not including the ballroom), and complete with a resplendent gold ceiling, gold-framed mirrors and floors covered with oriental rugs, tiger rugs and leopard rugs. (Photo credit: Cesar Romero Robles/Flickr)

In person, she was of medium height, plump, plain and olive-skinned, with black hair (later a black wig), and smallish grey eyes that missed nothing. She favoured dark colours and wore her diamonds rather as an idol bedecked for worship. At one dance, a diamond stomacher glittered on her blue velvet dress, in her black hair was a diamond tiara with diamond stars, several diamond necklaces studded with immense collet diamonds hung around her neck, clusters of diamond bracelets wreathed the wrists of her long white kid gloves, and from her ears hung long diamond earrings.

The years of her reign were known as the Gilded Age, so immense were the fortunes made and spent. In the huge mansions along Fifth Avenue were marble mantelpieces, Gobelins tapestries, bronzes, sculptures and paintings swept up from Europe, oriental carpets, crystal chandeliers, and French Furniture. At parties, houses were smothered with flowers, and party favours were antique ivory fans, gold snuff boxes or sapphire stock pins, with hundred-dollar notes stamped with the host’s name wrapped around cigarettes.

But the highlight of the entire social year was Caroline Astor’s ball. Its keynote was ceremony and lavishness – you went there to be seen. Her parties also featured another lavish and unusual feature – a midnight supper. The dancing would be halted, and little tables would appear, and a sumptous supper served by servants in green plush coats and white breeches, with buttons sporting the family motto.

The ballroom, where Mrs Astor’s legendary annual balls were held. Completely covered in artwork, the ballroom could comfortably hold 400 people, which led to the speculation that it was the reason why the list of New York’s wealthiest, most famous and most powerful was capped at 400.

The ballroom, where Mrs Astor’s legendary annual balls were held. Completely covered in artwork, the ballroom could comfortably hold 400 people, which led to the speculation that it was the reason why the list of New York’s wealthiest, most famous and most powerful was capped at 400.  A faux fireplace is the centrepiece of the ballroom, a modern take on the exquisite gilded fireplace that sat in the original Astor mansion. Caroline’s Mansion can seat up to 180 guests in banquet seating style.

A faux fireplace is the centrepiece of the ballroom, a modern take on the exquisite gilded fireplace that sat in the original Astor mansion. Caroline’s Mansion can seat up to 180 guests in banquet seating style.

The nouveau riche outside of Mrs Astor’s social circle would go to any lengths to acquire an invitation. Either pleading through a third party, persuading Ward McAllister that they had a grandmother of impeccable lineage, or hosting their own soirees, which were duly written up in the social columns of the day. Others, to avoid the stigma of not being asked, would get their doctors to prescribe a trip for their health’s sake. After all, it sounded much more elegant to say, “I’m taking my daughters to be educated in France,” than “Mrs Astor hasn’t asked me to her ball.”

Staying at or near the top was a constant struggle. Even in the Astor clan there was in-fighting. For years, Caroline’s nephew William Waldorf Astor fought a running battle with his aunt to try and position his wife Mamie as the Mrs Astor – after all, he was the eldest son’s eldest son, so his wife should hold the position. But nothing could dislodge Caroline, even when her nephew had his father’s house torn down and replaced by an enormous hotel (the Waldorf Hotel), designed to overshadow his aunt’s mansion beside it. As she famously said in an icy put-down, “There’s a glorified tavern next door.”

The entrance of the new Caroline’s Mansion at St. Regis Singapore.

The entrance of the new Caroline’s Mansion at St. Regis Singapore.

The foyer area of Caroline’s Mansion (right) was modelled after the stair hall of Mrs Caroline Astor’s Fifth Avenue residence (left). (Photo credit: The Gilded Age Era/Blogspot)

The foyer area of Caroline’s Mansion (right) was modelled after the stair hall of Mrs Caroline Astor’s Fifth Avenue residence (left). (Photo credit: The Gilded Age Era/Blogspot)

Socialite Alva Erskine Smith, first wife of railroad and racing tycoon William Kissam Vanderbilt, was one of the few people to outwit Caroline Astor on her own ground. She first built an enormous mansion on Fifth Avenue and filled it with treasures. Then she announced that she would host a housewarming costume ball, with the guest-of-honour her friend Consuelo Yznaga, who was married to the Duke of Manchester’s heir, Lord Mandeville. Society, avid to see the inside of the new house and meet a future duchess, eagerly accepted her invitation.

Suddenly Caroline Astor, accustomed to being asked to everything, realised she did not have an invitation. Her daughter, who had practiced her cotillion for months, would be unable to perform it. When she let this be known, Alva declared that she could not make such an approach because the rule was that the senior lady must first have called on the junior one.

At once, Mrs Astor dispatched her footman to leave a card with Alva, and almost by return, an invitation was sent down Fifth Avenue. Mrs Astor attended the ball, saying afterwards, “We have no right to exclude those whom the growth of this great country has brought forward, providd they are not vulgar in speech and appearance. The time has come for the Vanderbilts.” The Vanderbilts were fully accepted into the upper echelons of New York society.

The two ladies who managed to outsmart Caroline Astor: Alva Vanderbilt (left), pictured here in a portrait from a fancy dress ball in 1883, who outwitted Caroline for a coveted invitation to her exclusive ball, thus securing the inclusion of the Vanderbilts into New York society's inner circle; and Grace Vanderbilt (right), pictured here in a 1909 photograph, her protégée who staged a coup de grace that led to her downfall from the New York society. (Photo credits: Alamy and Vanderbilt Mausoleum and Cemetery)

The two ladies who managed to outsmart Caroline Astor: Alva Vanderbilt (left), pictured here in a portrait from a fancy dress ball in 1883, who outwitted Caroline for a coveted invitation to her exclusive ball, thus securing the inclusion of the Vanderbilts into New York society's inner circle; and Grace Vanderbilt (right), pictured here in a 1909 photograph, her protégée who staged a coup de grace that led to her downfall from the New York society. (Photo credits: Alamy and Vanderbilt Mausoleum and Cemetery)

It was not until 1902 that Caroline Astor was finally toppled. Her nemesis was 32 year-old Grace Vanderbilt, originally one of her protégées, who outflanked her in a ruthlessly cunning move that resulted in Grace, rather than Caroline, entertaining Prince Henry of Prussia to dinner. It was the coup de grace. As the shockwave travelled around New York, Caroline left for Europe, much like the other women who had tried and failed to receive an invitation to her ball.

Or as the gossip magazine of the day gleefully put it, “Mrs Astor will sail before the dinner takes place.”